- Muslims in Xinjiang, China, are being surveilled and locked up en masse by regional authorities who see them as terrorists whose religion are akin to a disease or cancer.

- Meanwhile, India revoked the autonomy of the mostly-Muslim region of Jammu and Kashmir, and is building detention camps for ethnic Bengalis – most of them Muslim – in the northeastern state of Assam.

- There are several parallels between these two countries’ actions – both claim their projects are to prevent violence and explicitly told other countries to butt out of their affairs.

- The rest of the world is too powerless to stop these economic powerhouses from continuing their mass internment projects.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

China and India, two economic powerhouses with some of the largest populations in the world, are brutally oppressing their ethnic and religious minorities. But the international community is loathe to rebuke them.

In Xinjiang, Chinese authorities have installed the equivalent of a 21st-century police state, with the Uighur ethnic minority monitored by electronic spyware, and locked up en masse in prisons and detention camps. Uighurs call the region East Turkestan.

In August, Indian authorities revoked the semi-autonomy of the disputed territories of Jammu and Kashmir, and placed the region under an internet and phone blackout that largely remains today.

Residents – many of whom are Muslim – have been placed under virtual house arrest, unable to worship on holidays or harvest crops.

In Assam, northeast India, officials are also building internment camps to hold hundreds of mostly-Muslim ethnic-Bengalis, whom the state has declared illegal immigrants because their names are not included on the National Register of Citizens.

Many of them have lived in India their whole lives, but their citizenship documents are nonexistent, lost, or riddled with spelling errors. Indian authorities said this week they want to extend the policy throughout the country, making activists grow more fearful for Muslims' safety.

"In Assam, the camps are currently set up within existing prisons," Angana Chatterji, co-chair of the University of California, Berkeley's Initiative on Political Conflict, Gender, and People's Rights told Business Insider.

"Reportedly about 600 to 700 people are being held in them," she said, adding that the prisons and camps being built "are being likened to concentration camps."

Though Xinjiang, Kashmir, and Assam are hundreds of miles apart, they all seem to follow the same playbook.

Both countries target Muslims to 'prevent violence'

China has repeatedly claimed that its actions in Xinjiang are a counterterrorism measure, and even cites Islamophobia to justify its actions. Leaked Communist Party documents, published last week by The New York Times, shows authorities referring to Uighurs' religion as a cancer, disease, or drug addiction.

Meanwhile, India's External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar has said the country cut off Kashmir's internet and communications to fight radicalization and "prevent the loss of life." Locals and law-enforcement officials have been involved in violent clashes, and thousands of people have been detained.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government, which is built on Hindu supremacy, has also capitalized on local Hindu suspicion in Assam of ethnic Bengalis, who have different ethnic identities, religions, and languages, said Meenakshi Ganguly, the South Asia director of Human Rights Watch.

Amit Shah, the country's home minister, has referred to illegal Muslim immigrants in India as "termites" and threatened to throw them into the Bay of Bengal. The government has justified its actions in Assam as a matter of national security.

Ethnic tensions are an 'internal matter'

Both China and India have batted away international criticism by insisting that those issues are internal matters - and to an extent, their tactics are working.

The Chinese government forbids foreign journalists from entering Xinjiang to report, opting instead to organize heavily-choreographed and chaperoned tours to the region that involve bizarre performances of Uighurs dancing or learning Chinese in classrooms. At least two such trips have taken place.

Beijing has repeatedly dismissed reports of physical and psychological torture in those camps, claiming instead that they are "free vocational training" - even though many of the detainees doctors, journalists, or other professionals.

India, meanwhile, has repeatedly said that the Kashmir issue can only resolved bilaterally between India and Pakistan, citing two historic agreements on the matter. The issue of illegal immigration in Assam and elsewhere is a matter of national security, according to Indian politicians.

In October, Indian authorities took a group of mostly right-leaning Members of the European Parliament on a tightly-controlled trip to Kashmir, which included a stay in a luxury hotel and a peaceful boat ride, the BBC reported. The delegation did not witness any clashes or detentions.

But Sen. Chris Van Hollen, a vocal critic of Indian policy in Kashmir, was barred from entering Kashmir during a trip to India in early October.

"I was told it was not a good time" by Indian authorities, Van Hollen told Business Insider. "India's actions are fueling the more extreme elements on the ground," he added, referring to anti-India militants in the region, many of whom are funded by Pakistan.

Darren Byler, a Uighur expert and University of Colorado researcher, said the Chinese and Indian government tours are likely helping quell foreign criticism.

"I think the people that go on those tours, they understand that this is being staged for them, at least to some extent," he told Business Insider.

"But they also see it as a way of justifying, saying they've done their due diligence, and they've taken a look at what's happening on the ground - so they can sign off, check the box, to say they've looked into the box, and say there's nothing there."

Criticism will not be tolerated

China has repeatedly batted away criticism over Xinjiang, saying that its policies helped clamp down on terrorism and violence in the region. Shortly after The Times published the leaked Uighur files, the Chinese foreign ministry said its tactics in the region were "worth learning from."

India, meanwhile, has embarked on a disinformation campaign regarding Kashmir, accusing the BBC and Reuters of lying about massive protests in the region even though they were recorded on video.

While both China and India's actions are driven by nationalism, it's important to note that they're not coordinating on tactics - the two countries have an extremely complicated relationship, due in part to China's encroachment near Indian territory and its friendly relationship with India's main rival, Pakistan.

Too big to punish

Another similarity between the Xinjiang, Kashmir, and Assam crises is the lack of tangible, international action against them.

Not a single Muslim country is standing up to China over its actions, either to preserve existing economic ties or in response to Chinese threats to suspend future investment. Many Western countries have publicly criticized China's actions in Xinjiang - but have taken limited steps to stop the atrocities.

The European Union, for example, has told China to "change" its actions but has not taken any tangible steps to ensure it. The 28-nation bloc lacks a coherent view toward China - and Beijing has capitalized on this disunity by pitting EU countries against each other to prevent a united policy that could hamper its plans.

Last month the US Commerce Department blacklisted 28 Chinese companies, including eight highly-valued AI startups, in response to their role in the "implementation of China's campaign of repression, mass arbitrary detention, and high-technology surveillance" against Muslims in Xinjiang.

The sanctions were hailed as a good first step, but there is no evidence of change in China's activities, or any indication that the US will take further measures.

An executive at Dahua, one of the sanctioned tech firms, even appeared to celebrate after the announcement, telling a business newspaper: "The fact that we are under the US control list shows that we indeed have a strong technological capability."

"I think there's a lot of rhetoric - people want to care, they want to project that they're caring, but when it actually comes down to some kind of human or economic cost, they're not willing to take that step," Byler, the Uighur expert, said.

"They also point a finger at the Muslim-majority countries, saying: these countries aren't even taking a stand at all, or they're supporting the Chinese state," he added. "So that helps them feel justified in saying, 'at least we're condemning it, we've taken that step.'"

Aside from written statements of concern, the US has not taken any concrete action against India over its crackdown in Kashmir and Assam either.

The House Asia subcommittee held hearings on human-rights violations in the region in late October, and the US Commission on International Religious Freedom issued a report this week noting their concern over India's using the citizenship list to tacitly set a religious requirement on citizenship and oppress Muslims.

The US is also "highly unlikely" to impose economic sanctions on India over Kashmir, a former US diplomat specializing in South Asia told Business Insider, noting that Washington hasn't sanctioned Pakistan for harboring militants in Kashmir either. The source had declined to be named due to the sensitivity of the issue.

But "that doesn't mean that it's okay to apply a communications blockade on an entire region, and put a bunch of people who are mainstream politicians and who used to be in alliances with the ruling Indian government, into preventive detention," the person said.

An appropriate venue to raise India's actions in Kashmir would be at the UN Human Rights Council (UNHCR) the diplomat said.

But the fact that the US, the most powerful country in the world, quit the UNHCR - calling it "hypocritical and self-serving" - has effectively neutered its leadership in human rights and leverage to condemn India's human rights abuses.

There is also evidence to suggest that UNHCR condemnations don't work: Earlier this year 22 mostly-Western countries wrote a joint letter slamming China's "arbitrary detention and restrictions on freedom of movement of Uighurs, and other Muslim and minority communities in Xinjiang."

The harsh language of the letter was outweighed by 37 other countries - including Syria and North Korea - standing up for China.

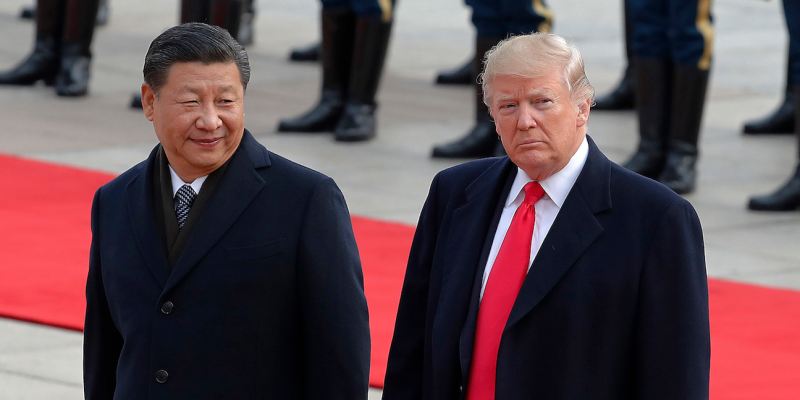

And in September, amid the Kashmir blackout and Assam's citizenship crisis, Trump hosted Modi at a rally in Houston, Texas, where Modi defended his government's actions in Kashmir.

What China and India are doing to their Muslim minorities is bleak. But without powerful countries and international bodies willing to take a stand, these persecutions are likely to continue unimpeded.